Lehman, Brexit, De-Regulation and the future of EU fintech

Lehman, Brexit, De-Regulation and the future of EU fintech

The decision by the citizens of the United Kingdom to vote against continuing membership of the European Union (#brexit) will have wide ranging repercussions on many facets of the European (and even global) economic system. As of early 2017, we see this trend further reinforced by a new US administration that aims to revisit a wide range of policy choices, including aspects of financial services regulation. While the aftershocks of these events still reverberate, it seems that we can posit quite confidently that:

One of the most dramatic impacts of these political events will be a radical reshaping of how financial services will be organized within the European Union.

Our near future includes a large set of possible scenarios: from the #brexit result being reversed in essence (although - as of early 2017 - this looks unlikely) all the way to further countries defecting from the European Union (as of early 2017 remains to seen). Given the fluidity of the situation (including further political uncertainties within the EU itself), how secure is this assertion? There is no simple answer to this question. It helps if we first backtrack - quite a bit - to trace how the European financial system came to have its present complicated shape. Our best chance to forecast correctly the near future is to try to understand the recent past. The success of this approach is based on the fact that many historical patterns tend to be persistent (repeating). So while, forecasting is never easy, if we manage to identify a pattern that is long-lived, we have a fighting chance that the forecast is better than a random guess (In econometrics this type of behavior is termed auto-regression). So the question we tackle in this blog post is: what are the autoregressive features of the European financial system?

While politics is volatile on a four year timescale, technological evolution and diffusion is intrinsically less so. It is precisely the tracing of the historical patterns around the development and adoption of financial technology that gives us a fighting chance to understand where we might be heading with financial services in the European Union.

The invention and diffusion of financial technology (fintech)

While currently the term fintech is very trendy, financial activity was always relying on technology. Lets clarify what we mean by technology in the financial sphere, because all too frequently it is being understood in a too narrow sense. Whether it concerns payments, lending or insurance, Finance is a combination of the following elements:

- External artifacts: This is the physical basis of finance, including everything from clay tablets and paper records, to supercomputers and digital communication networks. This is the material backbone that enables the capture and sharing of economical activity as data.

- Transactions, accounting and risk management activities: This is actual formalized manifestation of financial activity by participants. It takes the form of procedures where people use artifacts to enable or facilitate sophisticated economic activity (exchange of goods and services, contracting and risk transfer etc).

- Rules and societal conventions: This is the corpus of laws, regulations and social norms of accepted and/or desired economic behavior. This is a context layer that provides a boundary (limit) to the otherwise huge set of possible procedures that can be supported by any given technology infrastructure.

Tracing the future of EU financial services requires understanding how the above key building blocks of finance will evolve in the near future. What artifacts will be deployed, what kind of value and risk transfers will Europeans choose to undertake using them and how will this infrastructure be monitored and controlled? Luckily we don’t need to dig very deeply to figure out what has been a persistent pattern of how financial services have been evolving in the recent past:

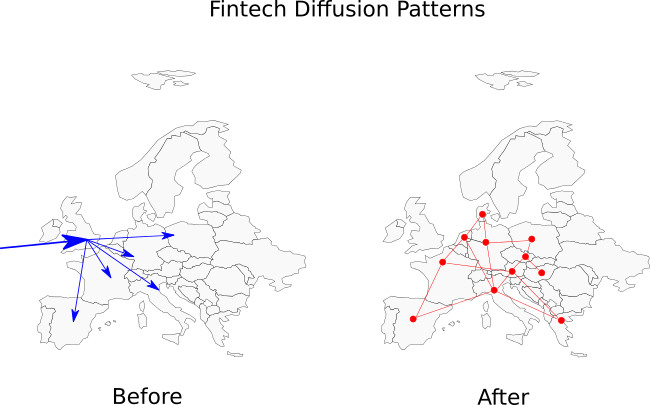

For at least the last forty years, the United States has been the world's main exporter of financial technology and Europe has been by-and-large a net importer

A full review and support of this statement would take quite a bit more than a long blog post, but it should suffice for our purposes to mention a couple of well known examples: Both securitization and financial derivative contracts, two of the most powerful recent innovations in financial technology where developed and first adopted en-masse in the US, starting around the seventies-eighties. This was actually the first fintech period of the recent era, so lets call it Fintech 1.0.

Lehman and the era of Excel Finance

Europe has been a net importer of this US led revolution. London was the epicenter of a technological diffusion process. Within the confines of the square mile cauldron, three constituencies (US, UK and continental European bankers) worked together to forge European versions of Fintech 1.0. This included developing various local securitization markets, an over-the-counter derivatives market etc. Yet the adoption rate of this - then - new financial strand in the continent was stubbornly slow. Pre-existing financial technologies (namely traditional commercial and retail banking, lets call it Fintech 0.0) continued to be in widespread use.

An important point is that the cause for slow diffusion was not the lack of artifacts. While not trivial, the tools to facilitate Fintech 1.0 were easily available from US providers (for example the first generations of digital databases). In fact in many cases the main purported required artifact for participating in this new era was familiarity and use of Excel, a fantastic piece of software, also readily provided by a US software giant.

The rate of adoption did hinge, though, on the willingness of European states to reshape the legal and regulatory environment around finance (the third pillar). Reshaping this environment would enable a migration of procedures and practices from the prevalent banking based finance (bilateral, banking license based) to the capital markets based finance (transactional, multi-lateral, rating agency based). This was a slow ongoing process with different degrees of adoption in different European countries. Needless to say that this process was interrupted completely by the 2008 crisis.

The Lehman event revealed fatal flaws in the technical, procedural, legal and regulatory frameworks around securitization and derivatives (key pillars of Fintech 1.0). This occurred first at the originating jurisdiction (the US) where presumably the implementation was the most sophisticated and mature. The crisis signaled also the end of Excel finance, a period where financial intermediaries could pretend to be sufficiently on top of the required information flows using an excel spreadsheet worth of data.

For Europeans the crisis was an embarrassing moment where their newly purchased cool financial gadgets suddenly exploded in their hands, much like overheating smartphones. What ensued was a rapid re-nationalization of finance and a retrenching within individual country borders. The importance of this re-localization phenomenon for the future of European fintech cannot be overemphasized: Finance (and financial tech) needs an ultimate backstop. When disaster strikes it messes up the artifacts, disrupts economic activities and renders the control framework obsolete. Given that our entire monetized livelihood is captured within this system, explicit and implicit guarantees are required to enable the system to repair itself with minimal damage. The only credible source of such guarantees is the entirety of a given society, the collective.

In the aftermath of the crisis the entire European financial system has been in low temperature life support. Emphasis was placed in stabilizing the existing fintech technologies. The most clear example being the rapid implementation of the Eurozone Banking Union, which, while still unfinished, is unprecedented in the scope and rapidity of its implementation.

For the City of London, the 2008 crisis was the first dramatic setback in its role as a European transplantation clinic for US financial innovations

The crisis showed that off-shoring European finance can have dire financial stability implications. Almost a decade after the onset of the crisis, discussions about reviving the US inspired Capital Markets Union, were just about about restarting

Brexit put suddenly the proverbial nail on the coffin on the nascent Fintech 1.0 European revival plan. Lets be clear: the artifacts and procedures of capital markets based finance are just a set of technologies. Like all technologies, they can be put to useful or wrongful use and much depends on the right control context (the third pillar of finance). Yet that control framework, being the only protection before the collective becomes liable, cannot possibly be served in any significant manner by intermediaries operating from offshore jurisdictions. If and when more widespread adoption of Fintech 1.0 type technologies happens in Europe, it will be based far more heavily on home-grown ingredients.

Brexit, Fintech 2.0 and the era of Cloud Finance

In the meantime a new wave of IT innovations emanated out of the US. The (old) Microsoft era is over. A set of new technology powerhouses (GAFA = Google, Amazon, Facebook, Apple) are rapidly transforming how all information is digitized, processed and used. Key features of this new wave is the increase in the volume and rapidity of data collection and processing. Another major innovation is the more profound use of linked digital networks. With finance being almost exclusively an information management business, it became quickly clear to many that

Financial technology will be completely reshaped through the newly available information technologies, a phenomenon termed Fintech

It is not surprising that London jumped on this second generation Fintech (2.0) with just as much gusto as with the first incarnation. The transplantation pattern was known. The newly invented IT toolkit was again readily available from US providers. There was plenty of underutilized financial talent to tap as well... Prior to Brexit it looked for a moment as if there would be a second chance for London to become the predominant provider of next generation financial services to Europe. While the legal/regulatory/political component that would allow this to happen was definitely not yet in place, UK authorities were hoping to pro-actively nurture the new fintech sector into a viable proposition. This is when history intervened to the detriment of the new blueprint.

Alas at the very core of the stated motivations for Brexit was for the UK to avoid perceived burdensome EU regulations and the jurisdiction of the European Court of Justice. If there was even a slim chance that light-touch Fintech could be a viable export into European markets post the Lehman moment, post the Brexit moment that chance has been reduced to precisely zero.

How will Europe respond to the need for efficient and stable financial services?

Europe cannot forever rely on others to provide it with fitting solutions to its financial infrastructure. There is now a backlog of no less than three unfinished fintech revolutions in the common European economic space. To enumerate:

- Euro-Fintech 0.0: a sprawling banking system: filled with non-performing loans and a bizarre unfinished banking union design that cannot handle intra-European sovereign risk

- Euro-Fintech 1.0: an underdeveloped capital markets based financial system: looking increasingly leaderless with few champions outside London

- Euro-Fintech 2.0: a nascent digital network based financial system where practically everything still needs to be invented, tested and deployed

History has thrown down the gauntlet. How will the EU financial sector respond? The new, US invented digital technologies provide practically limitless possibilities for re-organizing any of the currently known versions of fintech (and probably enable some versions not known yet). Yet it is upon individuals active in the EU financial services sector to internalize the rapid fire technical innovations coming from the other side of the Atlantic and mold them into procedures and conventions fit for EU use.

The track record is not promising for speedy progress but there is a possibility for surprise at every turn! One thing is for sure: There will be no help from the outside in cleaning up the European Union’s diverse fintech mess. The US is a single legal, economic and cultural space. Solutions developed there will reflect and serve the needs of US citizens (the same applies to the other emerging fintech giant, China). The EU is instead a unique two-tier structure of member states, which nevertheless chose to collaborate closely for common benefit. The unique nature of the EU means that for both old and new financial services platforms to scale and benefit from the size of the common economic area they must reflect and serve that reality truthfully and effectively. Examples are the absence of risk-free Eurobonds, and the limited (but non-zero) appetite for cross-border risk sharing. Another small but significant example of real cultural differences: most EU citizens have significantly higher sensitivity versus data privacy. This preference will be a central design choice of any new European fintech platforms. These unique EU constraints should be just the starting point, not the end of the next EU Fintech era. While the shape and form these will take are completely open, one key design aspect we can predict with complete confidence:

each individual polity comprising the EU will have to own, understand, trust and back the Euro-Fintech frameworks unequivocally.