9 Things They Do Not Tell You About Risk Management

Risk Management means different things to different people. In this post we explore some truths about professional risk management that highlight both the challenges it is facing as a discipline and the significant role it can play towards a sustainable future

9 Things they do not tell you about Risk Management

1. Risks don’t fall from the Sky. They are generated by other People

Informal Risk Management has been practiced by individuals since time immemorial. This is the domain of intuitive decision-making, assessing a situation on the spot and taking immediate action to avoid obvious risks.

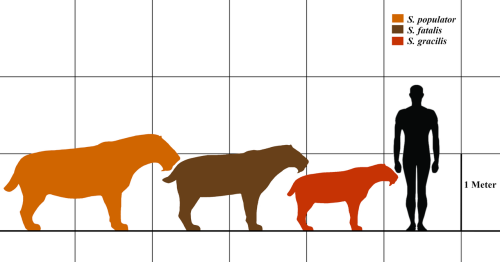

Over aeons such empirical risk management has collected a treasure trove of heuristics, rules of thumb and colorful Risk Management One-Liners such as: There is never only one cockroach. Yet long-gone are the days of hunter-gatherer societies facing the threat of sabre-toothed tigers. In modern societies many of the old risks we have been faces have actually been mitigated . The majority of risks faced by individuals today are created and shaped, directly or indirectly, by the social and economic context in which people find themselves.

This is particularly true for companies - which are entirely virtual and legal creatures, thus socially defined. Consider the main risks managed by a modern company, especially in the financial sector: This includes Business Risk , Credit Risk , Market Risk and a host of possible other risk types .

What all these risks share in common is that they have little to do with physical risk factors. In fact, a quick-scan of an entire typical Risk Taxonomy suggests that old-fashioned physical risks are but a small fraction of all risk types. Even the fundamentally natural risk factors (such as floods, wildfires, hurricanes etc.) have nowadays a strong human flavor: They are generally well known and understood risks and the degree to which they represent Residual Risk depends quite strongly on our Risk Appetite .

Extrapolating to the biggest current risks we are facing (the long-term sustainability of the human enterprise) these risks too are the result of “other people”, namely all of us. They emanate e.g., from our ability to affect collective behavioral change, overcome narrow vested interests and avoid false transition paths . These are all effectively endogenous and, in-principle, controllable characteristics.

The implication of the human-made nature of most risks is that formal Risk Management , namely the techniques, practices or behaviors that aim to identify, measure and mitigate risks to an individual or an organization must draw from a mix of social and hard sciences and avoid the Pretence of Knowledge .

2. Every Risk Ranager has at least Two Blind Spots

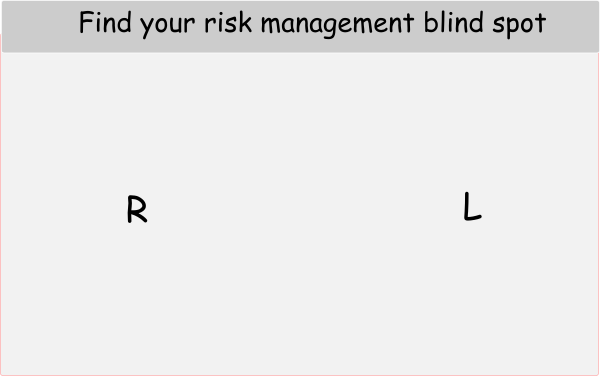

As a reminder, the blind spot of the human eye is an actual small circular area at the back of the retina where the optic nerve enters the eyeball. It is devoid of rods and cones and thus it is not sensitive to light. The blind spot is normally passing unnoticed for individuals with two functioning eyes. The simple visual test below, though, suggests we all have to live with our blind spots. If you haven’t done this test before, simply follow the instructions to convince yourself!

- Close one eye (say the LEFT one) and focus with the other eye (RIGHT) on the letter R. Notice the letter R is on the left side of the screen but you are supposed to stare at it with your right eye!.

- Place your head a distance from the screen approximately equal to three times the distance between the R and the L letters (No need to be precise!)

- Move your head towards / away from the screen until you notice the letter L disappear. Bingo! You’ve found your blind spot for that particular eye.

- Hints if you can’t find your blind spot:

- Try to focus on the letter and do not bounce your gaze around

- Don’t change position too fast

- Once you find your blind spot alternate your eye left and right for the disturbing realization that our common sense can actually easily betray us without any warning.

You can learn more about optical blind spots on Wikipedia, but for our purposes the exercise aims to suggest as a metaphor that many risks derive from (or get aggravated due to) intentional or unintentional ignorance.

Ignorance (namely risks hiding in the risk manager’s blind spot) may reflect either the ability or the willingness to be informed. Ignorance may take various forms:

- Mundane and common classes of risks are amenable to “knowing” - if one only would apply themselves to the task! In our blind spot analogy this would simply mean purposefully moving one’s eyes around rather than staring at the same spot.

- We can’t always remove blind spots: One common manifestation of unintentional ignorance is the perennial complaint by risk managers about the lack, or low quality, of Risk Data. Various practical reasons (e.g. cost) may prevent filling the gaps in the Risk Profile .

- Unknown-unknowns, black swans and other Tail Risk phenomena associated with fundamental Uncertainty are dominating discussions about the limits of risk management. Quite frequently this happens after significant and publicly visible risk management failures that prompt introspection and seeking culprits.

- Ideological blind spots can hide major sources of risk. Environmental sustainability is a prime example of such a mental blind spot. For centuries our living environment (the Biosphere) has been treated by both theoretical (economic) and practical (business) thought as an external “asset” that is simply there for the exploitation by the most entrepreneurial spirit.

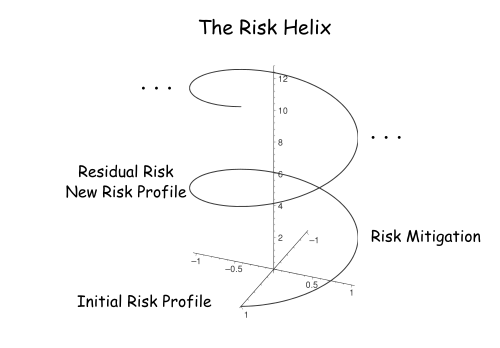

2. Risk Mitigation opens up the door to New Risks

Effective management of a given risk (using some form of Risk Mitigation ) can give rise to new risks in various ways. We are talking in this context about phenomena such as Residual Risks or Risk Compensation and even emergent behavior or Unintended Consequences. The result is that the job of the Risk Manager is never really “done”. After an initial risk profile has been modified (with whatever action has been applied), there is a new risk profile that related but is also distinctly different from the previous one, like a never-ending helix:

There are several reasons underlying this never-ending Risk Helix:

- Focusing on specific risk metrics may indeed help highlight and reduce a given quantum of risk - but this may eventually get manipulated (Goodhart’s Law ). It may also lead to risk buildup of a different type.

- Removing risk of one type may structurally generate another risk. For example, Risk Transfer using formal risk management tools and contracts may generate a new dependency or a systemic risk link. This arises from the mitigation mechanism itself (for example risks cumulating to the implicit or explicit “insurers” of risk).

- Risk compensation (adding more risk), because of the comfort and confidence that risks have been managed and are under control.

It is the task of good risk managers not to rest on their proverbial laurels and continuously be on the lookout of a mutating and transforming risk landscape.

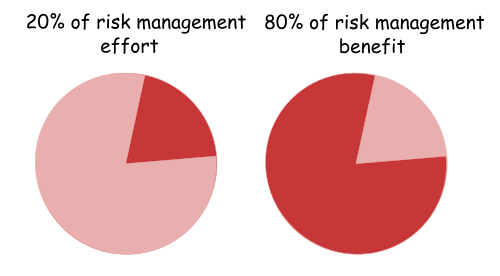

4. The Pareto principle (20/80 rule) applies

The Pareto principle states that, for many outcomes, roughly 80% of consequences come from 20% of causes. Other names for this principle are the 80/20 rule or, more formally, the principle of factor sparsity (the relatively small number of true factors). This principle is of vital importance for the practicing risk manager.

The manifestations of the Pareto principle are to be seen in many areas of Risk Management.

- The biggest risks usually lurk inside a few major exposures .

- The market price uncertainty of large numbers of securities can usually be explained by a small number of factors.

- The truly independent drivers of credit performance are fewer than the myriad of attributes tracked by credit systems .

This parsimonious distribution of the “real causes” of risk events may be in conflict with the professional incentives of Risk Managers, which may want to emphasize comprehensive analytical enumerations and/or the proliferation of checklists .

Zeroing-in on the stuff that matters is the surest way for Risk Managers to gain credibility with the stakeholders of the risk management process (but it must be stressed that it is not always possible to isolate such 20/80 factors).

5. Risk Quantification has unavoidable Pathologies

It is a basic expectation from stakeholders that Risk Managers will distill objective and relevant quantitative risk metrics to help support decision-making. Yet very few systems (typically only natural phenomena with little or no human interference) can be analysed with the rigor and longevity of method that is associated with physical laws. In risk management applications risk models fail regularly, sometimes spectacularly so. Manifestations of failing risk quantification abound in practically all domains where risk models have been applied (See post for earlier commentary).

This propensity for eventual failure of risk quantification is formally denoted as Model Risk . It is something that can be reduced through the labours of systematic Model Validation but it cannot be eliminated. The reasons for this are manifold, but typically reduce to this: risk management being an intrinsically social enterprise means that it is subject to the complexity, subjectivity and volatility of all things related to human affairs. Similar to another regularly faltering field, the art and science of economic forecasting, risk management is subject to the sin of physics-envy .

Here is a a well known example of design failure. The picture below illustrates so-called “Desire Paths” (ad-hoc footpaths carved by people in defiance of implemented paths). The architect has set the rules, limits and recommendations and assumed that people will stick to the formal paved paths. Yet the reality of collective decision-making created its own alternative.

Risk Managers must be comfortable handling this precarious state of affairs. Quantitative approaches have a limited shelf-life and must be continuously updated to reflect evolving information about “the system”. As mentioned, structured approaches to limiting model risk (Model Validation) can help ensure that the tools are used within their “envelope of safe operation” and their irreducible weaknesses are explicitly acknowledged and managed.

6. Risk Accounting and how it is different from Financial Accounting

Financial accounting is used widely by companies in their regular reporting. It focuses on capturing the “state of the world” as far as the organization is concerned, or at least the state of the world that certain stakeholders consider important.

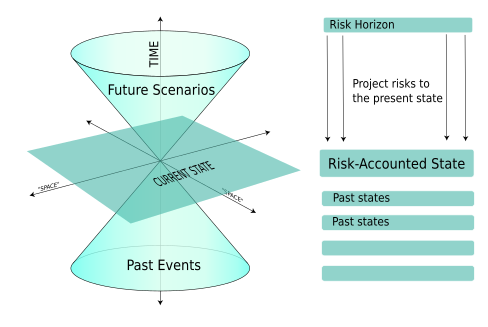

Financial reporting creates a snapshot of the present state of financial and broader economic affairs of a given entity. This creates transparency and supports decision-making. In addition, over time, it becomes a history of snapshots which can be analysed to provide further insights about the dynamics (evolution) of an entity.

Risk Management slices the world in a different way. While it, too, aims to support decision-making, it is oriented towards analysing potential future events. The questions asked by risk management and the decisions that hinge on these answers are always in relation to possible future events. Typical questions are:

- How likely that event or condition X will happen within Y years?

- What will happen if we change variable X by a Y amount?

- What is the worst that can happen to variable X if we do nothing for the next Y months?

The current and past historical record are useful for risk management only to the degree that they provide us with data and insights about the nature of system and its risks (and hence how it might evolve under different scenarios). Just as financial accounting provides a standalone picture of the present without reference to what might happen in the future, Risk Accounting aims to do the same after including a reference about the outlook of future states.

The tools for doing consistent, valid and useful Risk Accounting are preliminary (and even controversial). A major relevant example is the risk based accounting of credit risk (namely accounting for the risk that economic agents will not fulfil legal obligations of a financial nature). The worlds of risk management and accounting come together when one attempts to account for the present state of entities such as banks and insurers (under standards such as IFRS 9 ). These entities pursue risk taking as an essential element of their business model, hence ignoring such risks when reporting their financial state is less than full transparency.

How does risk accounting work? The algorithm can be stylized as follows:

- Start with the basic picture of non-risk adjusted facts

- Derive subjective (individual) or market based risk assessments (such as risk ratings or risk premia). These data points aim to express the future likelihoods of various scenarios.

- Average (derive the expected outcome) over “all possible scenarios” (this set is obviously just an assumption)

- Adjust the reported accounts to reflect these expectations

When considering the broader challenge of Sustainability Accounting we are still in a pre-embryonic stage: Financial reporting hardly address the externalities of economic activity in conventional accounting at all, hence it is quite premature to think about integrating and reporting sustainability risks on an expectation basis.

7. Risk Technology is essential for managing Risk in a complex world

The previous points may have suggested already that risk management is an information hungry (data intensive) pursuit. The past, present and future of potentially complex systems must be captured, represented and made amenable to analysis and “what-if” scenario questions in reliable, transparent and reproducible ways. This is generally a challenging task that increasingly employs digital technologies in significant ways. But given the quantification risks we discussed already, is such a RiskTech dimension at all necessary? Could the 20/80 principle we discussed already help us avoid ineffective and even misleading “sophistication” that simply generates new risks? The answer is firmly, No.

The necessity of effective risk information systems follows from simple considerations. Where does this need of masses of information come from? There are several very concrete drivers:

- The sheer size of human societies and economies (billions of individuals) and organizational structures.

- The uncountably large number of material and conceptual artifacts that are involved in daily life and the corresponding varying contexts they create for “risk-prone” situations

- The combinatorial nature of human affairs which drives dimensional explosions

Risk Technology is thus information technology that aims to create a “digital crutch” to help us cope with economic and social complexity. Its mission is to shape suitable tools to support the challenging task of capturing and delivering the information assets that can enable the risk management function. RiskTech is not a final solution for any risk management challenges. It addresses most effectively some aspects of the known-unknown type of risk (those that involve large amounts of data) by providing information processing tools (data, algorithms, visualization and representation tools) to enable risk analysis, risk accounting and thus (ultimately) informed risk management.

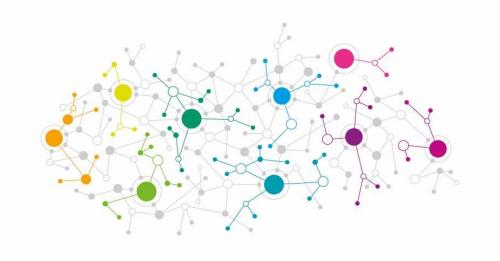

The limitations of RiskTech do not imply that it is a technique that is only useful when the risk landscape is trivial. But it does mean that it must integrate with human intelligence in structured and transparent ways. As an example: Exploring the systemic resilience of various environments typically cannot be done with actual experiments, but it can be emulated.

8. Risk Management is a Young Discipline with Limited and Fragmented Scholarship

Risk Management does not yet really exist either as a coherent knowledge domain or as an established profession in its own sake. It is always practiced within a sand-boxed and specific sectoral context. This fragmented landscape includes a few relatively more developed areas (such as financial risk management and insurance risk). These fairly developed areas concern specific risks types that are managed professionally by financial intermediaries, typically for-profit.

Analysing and underwriting well-defined types of risk is thus a core part of the business model of these sectors, but the principles, tools and methodologies of risk management are applicable to practically any and all facets of human life. Other sectors grapple with many of the same problems. Much of the quantitative basis of risk analysis based on statistics is actually common across fields. For example the medical sector has been historically leading the development of such techniques without ever naming them “risk management” tools.

There is a danger or “imperial overreach” when attempting to apply abstract conceptual frameworks to distinct domains. The devil is indeed in the details. But it is also sub-optimal to not connect the dots across different domains.

Connecting the dots (also known as Holistic risk management ) is in any case required by the mounting challenges facing modern societies. Transitioning towards sustainability requires expanding and connecting concepts of risk across a much wider array of domains than we have been accustomed to so far.

9. Risk Management is about the Future and its future is wide Open

We saw that Risk Management is a forward-looking, future oriented activity. It is information hungry and still an evolving discipline. While flawed and incomplete, it is constantly tasked with constructing plausible scenarios, shaping the untold multitudes of evolutionary paths into a manageable cone of uncertainty. Its main deliverable is to help us steer within the range of safe possibilities, in directions that better serve us as individuals or in collective undertakings.

This mental exercise of building fact-based models of the future has a bright and open future! Join us in this journey via any of the resources we are developing:

- Join our Open Risk Academy Courses

- Explore the Open Risk Manual

- Our open source risk platforms and models

Comment

If you want to comment on this post you can do so on Reddit or alternatively at the Open Risk Commons. Please note that you will need a Reddit or Open Risk Commons account respectively to be able to comment!