Towards a Faceted Taxonomy of Financial Services

In this post we are after a flexible financial services taxonomy that can help us understand both existing and evolving financial system developments. To this end we examine a range of existing classification systems and synthesize the salient requirements.

Who Needs a New Financial Services Taxonomy?

Our age is increasingly dominated by the dual challenges and opportunities of the sustainability transition on the one hand, and digital transformation on the other. We witness emerging new financial domains with novel names such as Fintech , or TechFin, or various combinations and hues of Green and Sustainable in Sustainable Finance and we see forces that are reshaping the direction of travel for the financial industry.

Understanding where and how the broader Financial System will be affected by these developments is of no small interest. Stakeholders are effectively all users of Financial Products , which means practically every economically active actor! A good example of renewed focus on “taxonomic” thinking is the EU Sustainable Finance Taxonomy an EU-wide classification system that aims to determine whether an economic activity is environmentally sustainable. Current Financial Service providers, are also keenly interested, since such systemic developments can drastically reshape business models. Last but not least, financial regulators and policymakers have the heavy burden of ensuring that these emerging financial system adaptations are fit-for-purpose. In a fully digitized economic system old fences and firewalls may no longer be relevant.

The motivation for thinking about classifications and taxonomies comes from the fact that analysing changing systems requires, at the outset, insightful, objective descriptions of their past and present states. In our focus area, a comprehensive description of a financial system would list its historically prevalent composite elements, their varied interactions and their success and failure modes and, hopefully, provide the means to identify common themes and structural patterns along which transformations might be happening. This is particularly relevant for sound and holistic Risk Management which is one of the core responsibilities of the financial system. A functional, fit-for-purpose financial services taxonomy is essentially a pre-requisite for a corresponding Risk Taxonomy and related developments are a long-term focus of our initiative.

In this context, a financial services taxonomy aims to provide a simple analytical tool that is but a small part of the harder task of sketching and understanding the complexity and vulnerabilities of the financial ecosystem. A taxonomy would be a categorization or classification of concepts associated with the broader economic phenomenon we call Financial Services. A taxonomy or classification is typically a hierarchical structure in which concepts (classes, or categories) are organized into groups or types of increasing specificity. Actual instances (exemplars) are eventually slotted within such classes. We will discuss more the formal requirements below.

In practice there is an incredible amount of diversity of financial practice across countries and sectors and there is no mechanism or authority that aims to compile such a complete, all-encompassing overview. Nevertheless, various existing taxonomies offer useful, even if somewhat partial insights that help us compile an interesting high-level picture and provide clues for what is needed next.

Our purpose as we review various financial system classifications and points-of-view is not to dive into their fine details but rather to distill clues about what a comprehensive and forward-looking financial services taxonomy might look like!

In a more technical and low-level vein, in the White Paper Connecting The Dots: Economic Networks as Property Graphs1 we have developed a quantitative framework that approaches economic networks from the point of view of contractual relationships between agents (and the interdependencies those generate). The representation of economic agent properties, transactions and contracts is done using the terminology and notation of mathematical property graphs. This toolkit is very expressive but flexible and low-level in its approach. Using the language of graphs we could say that in this post we are focusing on classification dimensions that are required to distinguish the various financial system nodes and relations between nodes.

We will dive straight away into an important exampleL: We start with the description of so-called “Shadow Banking” in relation to regular Banking.

How Shadow Banking sheds some light on Financial System Structure

Shadow Banking is the process of obtaining or providing bank-like financial services (savings accounts, lending) through non-bank financial intermediaries (NBFIs), that is, financial entities that are not formally regulated as banks. It is sometimes termed Market Based Finance and is prevalent in various jurisdictions across the world.

The analysis of shadow banking systems is a significant pre-occupation of Financial Regulators that are responsible for the supervision of financial system stability. The objective is to ensure that the operation of that system remains within mandated constraints and crises typically prompt in-depth studies of “what went wrong”.

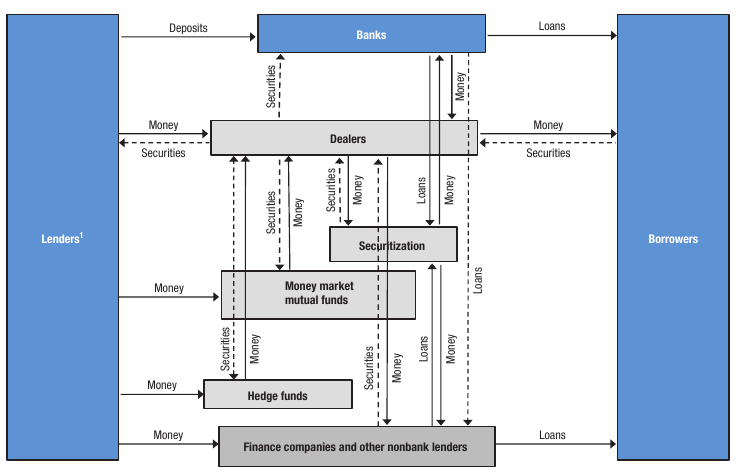

One of the most studied such systems, especially given the Lessons Learned from the Great Financial Crisis is the US shadow banking structure:

The above figure (from an IMF 2014 publication 2) illustrates the complexity of what is actually only a small subset of the US financial system. There are several important elements that we want to abstract from this diagram:

- The core economic needs (demand) and utility for certain financial services. In this instance, these needs are the lending and borrowing of funds.

- The corresponding principal economic actors that ultimately have those needs, namely lenders and borrowers, investors and entrepreneurs etc.

- The financial intermediaries that can fulfil these needs (banks, dealers, various types of funds etc.) in some combination of roles and functions

- The financial products (money, loans, securities) that are exchanged or bind the various actors via legally enforceable obligations and rights.

This decomposition is fairly fundamental and provides useful points for the further discussion. Yet it is by no means a complete picture: some important dimensions that are missing are:

- the nature and objectives of lenders and borrowers, e.g., the temporal duration of the economic relationships and exchanges (short, mid or long term?), or the use of proceeds.

- the complete internal structure of the intermediate “boxes”, namely the various financial intermediary entities, which determines economic objectives, value propositions, vulnerabilities etc.

- any reference to the specific types of real or financial assets involved, either as collateral or as being the main object economic interest (e.g. a lease contract). Such linkages are important e.g., when assessing externalities such as environmental impact

A Regulatory Financial Institutions Taxonomy

Another bird’s-eye view of the financial system is provided by the lists and taxonomies maintained by central banking authorities. For example, the high-level European Central Bank classification 3 includes the following categories:

Click to expand the ECB Classification

- Monetary Financial Institutions

(MFIs) - the money-issuing sector, which in turn includes

- central banks

- deposit-taking corporations except central banks

- credit institutions, the business of which is to take deposits or other repayable funds from the public and to grant credits for their own account

- financial intermediaries other than credit institutions, whose business is to receive deposits and/or close substitutes for deposits from institutional units (including from non-MFIs) and to grant loans and/or make investments in securities on their own account

- electronic money institutions, that are principally engaged in financial intermediation in the form of issuing electronic money

- money market funds, that is, collective investment undertakings that issue shares or units which are close substitutes for deposits.

- Investment funds (IFs) - collective investment undertakings that invest in financial and non-financial assets, excluding pension funds and money market funds

- Financial vehicle corporations (FVCs) - carrying out securitisation of other assets

- Payment statistics relevant institutions (PSRIs)

- payment service providers (including electronic money issuers) and payment system operators that offer payment services and/or are entitled to do so. They can be classified in different institutional sectors:

- credit institutions

- post office giro institutions

- national central banks

- state, regional or local public authorities

- payment institutions (meaning legal persons other than those listed above)

- Payment system operators are entities that are legally responsible for operating a payment system.

- payment service providers (including electronic money issuers) and payment system operators that offer payment services and/or are entitled to do so. They can be classified in different institutional sectors:

- Insurance

corporations (ICs) - providing pooling of risks, mainly in the form of direct insurance or reinsurance

- life insurance services, where policyholders make regular or one-off payments to the insurer in return for which the insurer guarantees to give policyholders an agreed sum, or an annuity, at a given date or earlier

- non-life insurance services to cover, for example, risks of accidents, sickness, fire or credit default

- reinsurance services, where insurance is bought by the insurer to protect itself against an unexpectedly high number of claims or exceptionally large claims.

- Pension Funds (PFs) - offering social insurance by providing income to the insured persons following their retirement

In the above ECB categorization we observe that the driving dimension of the taxonomy is primarily the type (sector) of the financial intermediary. The definitions are somewhat circular (the Insurance sector provides Insurance). Yet the classification identifies intermediary types that are indeed assumed to be active in bundles of related but distinct financial activities. Importantly, these entities are also regulated as such.

This point-of-view is also a partial classification scheme: The economic agents that are counterparties to the financial intermediation activities (the consumers of financial services) are not explicitly identified. They are implied by the sectoral classification. E.g., some financial intermediaries (Banks, Insurance) may cover a range of possible markets (so-called Retail, Commercial, Public Sector banking etc.) while others are by construction more focused to one type of end-user (e.g. Pension Funds).

We notice that the bundling of services in sectors can be rather convoluted: E.g., many different entities can provide payment related services. Further, conglomerate entities can provide a large menu of financial services (e.g. Bankassurance) and fundamental needs such as credit provision can be managed by diverse entities: banks, securitisation vehicles or credit insurers.

Regulatory Publication Categories

Sticking with the regulatory point-of-view a bit more, the Basel Committee produces an extensive collection of regulatory documentation BCBS Regulatory Topic Taxonomy which in many instances is adopted as legally binding regulation. This list of important topics provides further hints about the internal functioning of the banking system, at least as far as regulatory activity is concerned. The list of most relevant for our purpose categories is the following:

Click to expand the BCBS Report Classification

- Accounting and Auditing

- Anti Money Laundering (AML)

- Governance

- Compliance

- Disclosure

- Risk Management

- Climate-related Financial Risks

- Credit Risk

- Liquidity Risk

- Operational Risk

- Market Risk

- Interest Rate Risk

- Other Risks

- Financial Conglomerates

- Fintech

We observe that the categories featuring prominently in regulatory publications activity (NB: within the Banking sector which is the domain of the BCBS) are classified primarily by Risk Type and focus on the structure and critical functions of the financial intermediaries.

While not explicit in the above classification, it is worthwhile to note that some of these explicitly identified and regulated risks are managed by the financial entity as part of its added-value proposition. This includes the managing of liquidity, credit, market, interest rate risk. Other risks (in particular Operational Risk) are intrinsic to the operation of any corporate entity.

Taxonomy of Financial Regulators

If we invert the maxim Same Risk, Same Regulation, which is frequently mentioned in the context of a digital financial system involving many new “unclassified” actors, we obtain a taxonomy of the financial system as seen through the taxonomy of its current regulators. A simple inspection of the financial regulator universe 4 reveals the prevalent taxonomy of regulatory entities and their separation of duties:

- Banking Regulators

- Insurance Regulators

- Capital Markets Regulators

- Competition Regulators

- Consumer Protection Regulators

We see that the segmentation of regulatory activities in finance services mirrors in part the financial intermediary entities we have already seen (Banking, Insurance, Capital Markets). Yet there are two important additional cross-cutting dimensions that are of a different nature: Competition Regulation and Consumer Protection Regulation.

What do these cross-cutting regulatory categories reveal? At high level, this type of regulatory specialization reflects that the bulk of the financial system is i) a for-profit private enterprise which is supposed to act in, more or less, competitive market conditions and ii) individual persons engaging with the system may face significant asymmetries in information availability and/or ability to process available information (one recognized issue being limited Financial Literacy ).

The Fintech Landscape

We move next to discuss the classification of newly emergent digital channels that enable new forms of online financial activity (digital communication networks, mobile devices, internet-of-things devices etc.). Such developments add an important new dimension to the previous classification pictures and as already stated are in part motivation for re-examining the status-quo.

While some forms of digitization are already for many decades a reality in the financial industry (e.g. electronic bank accounts, mainframe databases, spreadsheets, the COBOL programming language etc.), important elements of the financial system were (and in places still are) essentially paper based, as seen for example in the use of legal contracts, the use of sovereign paper money etc.

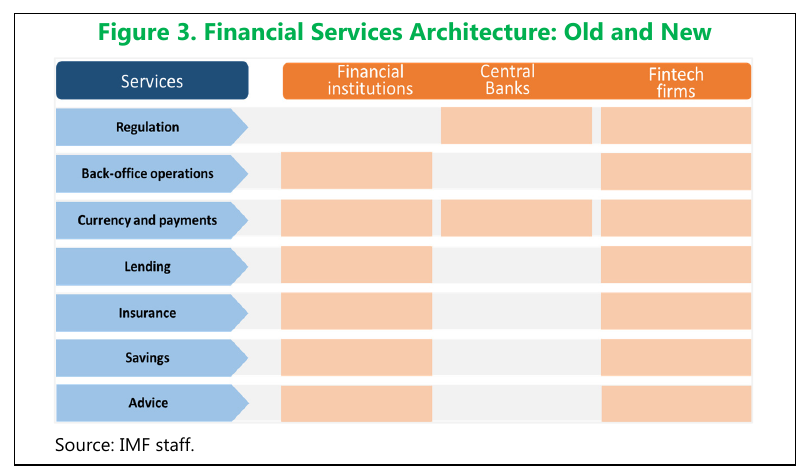

The underlying information technology used (i.e., whether paper-based or the different forms of digital technology) defines the capabilities and limits of the physical infrastructure that supports the financial system. This includes the shape and nature of physical locations (e.g. physical trading floors versus electronic market-places), and the ease and speed of accessing, processing and disseminating information etc. This situation is now rapidly changing. The following picture, from IMF, 2017 5 illustrates an emerging pattern where new types of firms (entities) can be involved in offering financial services of various types:

On the left hand side of this diagram we see a range of traditional financial services and on the right hand side domain in which new “digital” entrants are expanding. In this list, Payments , Lending and Savings and Insurance represent the classic financial services needs we have already seen but Advisory, Back-Office and Regulatory Services indicate an ever-growing collection of digitally instituted actors and activities.

Indicatively, we dive here deeper into one of these Fintech areas and explore in more detail the new categorizations of actors and activities in the specific subdomain of Payments . This will introduce us to the concept of unbundled financial service provision.

The Payment Services Directive (PSD2) and its Taxonomy

The Payment landscape evolves currently rather quickly in the context of purely digital transactions. The ultimate economic actors in the payments context are entities that would like to use a digital payment system (within or across monetary systems) to support their actual economic needs. The focus of the PSD2 directive is individual consumers (natural persons). The corresponding taxonomy recognizes the following entities:

- Account servicing payment service providers (ASPSP) which include:

- Credit Institution (Regulated Banks)

- Electronic Money Institution

- Post-office Giro institution

- National Central Bank

- Third-party payment service provider (TPPS) which are further split into:

- Payment Initiation Service (PISP) provider. Providing payment orders relating to an online payment account held with another payment service provider.

- Account Information Service (AISP) provider. Providing information on one or more payment service user accounts held with another or several other payment service providers

The pattern we notice here is the decomposition or unbundling of financial services activity in terms of constituent operations. The practical feasibility of such a decomposition owes largely to the flexibility provided by electronic transactions and platforms.

The digitization of the financial system has an important effect in enabling more granular definition and decomposition of the value-added by financial intermediaries. This is effectively enabling different actors to provide financial services that were earlier bundled within a more complex entity.

The BigTech Landscape

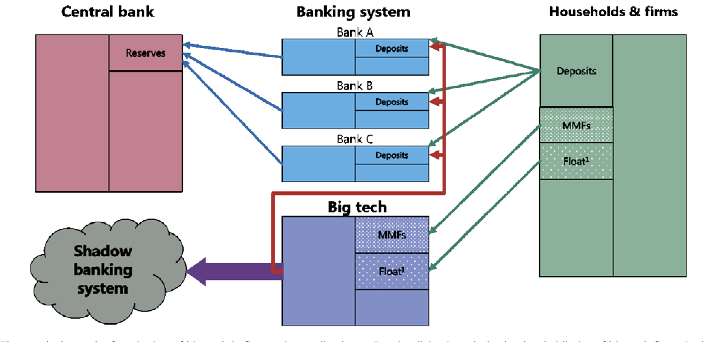

On the other extreme from the fintech startup ecosystem, a parallel universe that increasingly touches financial services is the so-called bigtech world, namely established and large digital technology companies that in various ways assume material financial system roles. The following picture is from BIS, 2018 6 and indicates how a technology platform can effectively create a digital shadow banking system.

In the above diagram MMF denotes online money market funds while float denotes duplicate money present in the financial system during the time between a deposit being made in the recipient’s account and the money being deducted from the sender’s account.

Big technology firms can bypass the traditional two-tier banking system where commercial banks make payments on behalf of clients and the central bank is the bank to the commercial banks. Said firms can also use captive funding to lend through the shadow banking system. Here we have again an example where the same underlying financial needs can be satisfied via different channels, involving different economic agents, different artifacts and tools and likely resulting in different risks.

Official Statistics Taxonomies

We now take a step back from the insiders view of the financial system and examine how official (economic) statistics and related spheres recognize financial system structures. Capturing the economic footprint of financial services domain happens in various official taxonomies. We select and review here a few representative ones which are widely used in Europe:

- The NACE system, which is a Business Sector (Economic Activity) Taxonomy

- The ISCO system, which is a Professions (Occupations) Taxonomy

- The CPV system, which is a Procurement (Purchase) of Goods and Services Taxonomy

The NACE Classification of Economic Activities

Financial services is an important economic activity, and thus it is captured in official statistics. The NACE Classification (Nomenclature of Economic Activities) is the European statistical classification of economic activities, established by law and used widely in various contexts. The system is hierarchical: at the highest level are broad industrial sectors such as Manufacturing or Mining which are refined at further levels, i.e. sector, sub-sector, sub-sub-sector etc. The relevant for us top-level section is NACE Section K which groups all financial and insurance activities as follows:

- K.64 Financial service activities, except insurance and pension funding

- 64.9 Other financial service activities, except insurance and pension funding

- 64.1 Monetary intermediation

- 64.2 Activities of holding companies

- 64.3 Trusts, funds and similar financial entities

- K.65 Insurance, reinsurance and pension funding, except compulsory social security

- 65.1 Insurance

- 65.2 Reinsurance

- 65.3 Pension funding

- K.66 Activities auxiliary to financial services and insurance activities

- 66.1 Activities auxiliary to financial services, except insurance and pension funding

- 66.2 Activities auxiliary to insurance and pension funding

- 66.3 Fund management activities

We observe that in this classification system, up to two levels of classification, financial activities are still bundling rather disparate economic activity elements. Even at the most granular levels, e.g., the NACE Class 64.19 - Other monetary intermediation , is defined as both the receiving of deposits and/or close substitutes for deposits and extending of credit or lending funds. A segment that clearly comprises several distinct economic activities and requires a large variety of different tools and expertise to perform. Lack of granularity is not a uniform feature of the NACE system. Compare, e.g., with NACE Class 15.12 - Manufacture of luggage, handbags and the like, saddlery and harness , which, after allowing for a supply chain of materials, is rather more focused.

Official statistical taxonomies that cover the entire economy might not have a consistent level of granularity that can resolve all the varied branches of economic activity to similarly elementary ones.

The ISCO Classification of Professions

A less conventional vantage point from which to look at the structure of the financial system is to focus on the professions (occupations) involved. While the providers of financial services have long ceased to be individual persons and now financial intermediaries may comprise thousands of individuals organized in corporations, the professional composition of these entities is indicative of the nature of economic activity that takes place inside them. Our guide in this direction is the ISCO Classification , the International Standard Classification of Occupations.

Exploring this classification we see that at the highest levels it primarily distinguishes the level of generality, specialization or responsibility of an individual (Manager, Professional, Technician, Clerk). It is at the lower levels of the taxonomy that one sees subject-matter specialization. For example, a full drill-down of the Manager class may produce the Bank Manager specialization:

- ISCO Major Group 1 Managers

- ISCO Minor Group 134 Professional Services Managers

- ISCO Unit Group 1346 Financial And Insurance Services Branch Managers

- ISCO Occupation Group 1346.1 Bank Manager

- ISCO Unit Group 1346 Financial And Insurance Services Branch Managers

- ISCO Minor Group 134 Professional Services Managers

As another example, we examine some technical specializations related to finance:

- ISCO Major Group 3 Technicians And Associate Professionals

- ISCO Minor Group 331 Financial And Mathematical Associate Professionals

- ISCO Unit Group 3311 Securities And Finance Dealers And Brokers

- ISCO Unit Group 3312 Credit And Loans Officers

- ISCO Unit Group 3313 Accounting Associate Professionals

- ISCO Unit Group 3314 Statistical Mathematical And Related Associate Professionals

- ISCO Unit Group 3315 Valuers And Loss Assessors

- ISCO Minor Group 331 Financial And Mathematical Associate Professionals

We see again a segmentation reflecting financial activities (e.g., securities or loans) and we get a glimpse of the specific know-how required from individuals (Accounting, Valuation, Statistical Analysis etc.).

The picture offered by the ISCO taxonomy is important, as it highlights both what are building blocks for composing a financial service and the possible adverse features linked to the incentives and internal and external relations of the individuals involved.

The CPV Classification of Goods and Services Procured

Related but distinct from the NACE Classification is the Common Procurement Vocabulary . This classification can be seen as a proxy for the range of financial services demand. CPV offers the legally valid code list that must be used when public entities in the EU area procure specific financial services. We find again that financial services is a sector already visible at the top-level (together with Insurance).

More precisely the relevant procurement taxonomy expands as follows:

Click to expand the CPV Classification

Division 66 - Financial And Insurance Services includes all financial and insurance services which are then organized as:

- Group 66-1 - Banking And Investment Services

:

- Banking

- Central Banking

- Deposit Taking

- Credit Granting

- Financial Leasing

- Payment Transfer

- Investment Banking

- Mergers and Acquisitions

- Corporate Finance and Venture Capital

- Brokerage

- Security Brokerage

- Commodity Brokerage

- Processing and Clearing

- Portfolio Management

- Financial Markets Administration

- Operational Services

- Regulatory Services

- Trust and Custody

- Trust Services

- Custody Services

- Consultancy, Transaction Processing and Clearing-House

- Financial Consultancy Services

- Financial Transaction Processing And Clearing House Services

- Foreign Exchange

- Loan Brokerage

- Banking

- Group 66-5

Insurance And Pension Services.

- Insurance

- Life insurance services

- Accident and health insurance services

- Legal insurance and all-risk insurance services

- Freight insurance and Insurance services relating to transport

- Damage or loss insurance services

- Liability insurance services

- Credit and surety insurance services

- Insurance brokerage and agency services

- Enineering, auxiliary, average, loss, actuarial and salvage insurance services

- Pensions

- Individual pension services

- Group pension services

- Pension fund consultancy services

- Insurance

- Group 66-6 Treasury services.

- Group 66-7

Reinsurance services.

- Life Reinsurance

- Accident and Health Reinsurance

We see that the CPV system offers in places more granularity than the NACE system but is, broadly speaking aligned. We also need to keep in mind that this classification serves Public Procurement (thus public sector legal entities). The financial service needs of individuals and private sector entities might differ in nature and detail.

Yet more other Points of View

We now explore a few more points of view in the hope that we might shed further light from different angles.

The FIBO Taxonomy and Ontology

The Financial Industry Business Ontology (FIBO Taxonomy ) is an ambitious project that aims to define sets of concepts that are of interest in financial business applications and the ways that those concepts can relate to one another. Note that it is an Ontology, not a Taxonomy. An Ontology is a logical structure that is more elaborate than a taxonomy or a classification scheme. It may, for example, include logical relations between concepts (e.g., a Mortgage is a Loan that references Real Estate Collateral) that represent more complicated associations than a simple is-part-of or is-special-case-of type relations that characterise a typical taxonomy.

Isolating the most relevant for our purposes FIBO categories we see the following concept groupings:

- Foundations

- Business Entities

- Financial Business and Commerce

- Collective Investment Vehicles

- Securities

- Loans

- Indices and Indicators

- Economic Indicators

- Market Data

The above grouping is somewhat uneven as a standalone classification scheme, but it highlights some interesting alternative dimensions, namely the nature of certain information flows and related artifacts (the need for Indicators and Market Data). Such information artifacts must be produced as part of solving financial needs and, in a sense, represent some important value-added of the financial system.

Unbundling the Credit Provision process

Finally, we perform a quick dive into the Credit Provision process, which is a narrow but important and widespread financial need. Credit provision is a complex business with detailed sub-processes and conventions which determine important data flows and assessments, all within fairly rigid legal and accounting frameworks (See Open Risk White Paper 09 7).

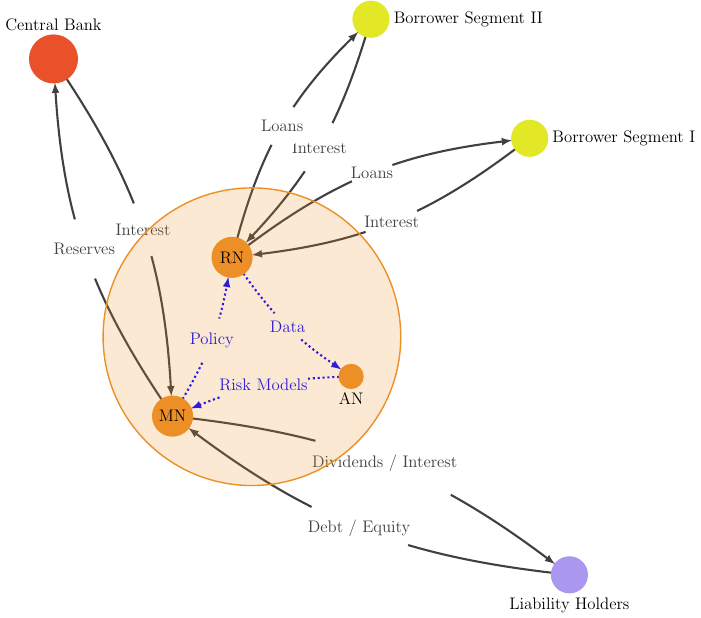

The functions and responsibilities of credit provision can be split into three business units (Monoline Businesses). The value proposition, the tools used, the liabilities and risks of these three entities are quite distinct. These units can also potentially exist as standalone businesses, in which case the provision of credit requires formal partnerships between such units. The three pillars are as follows:

- The Credit Relationship Unit. This is the core client-facing entity. It can be thought of as the credit providers physical or digital “front-end”.

- The Credit Management Unit. This is the core back-end of the credit provider, but can be also an external unit, acting as the key liability management entity (and the linkage to the rest of the financial system). This unit bundles many other key decision-making functions concerning the entire asset and liability portfolio that enables the lending activity. It also manages relationships with key stakeholders such as regulators and capital / liquidity providers.

- The Credit Assessment Unit. This is a “narrow purpose” node that performs primarily an analytic function in relation to credit risk. Yet that fairly narrow function is one of the cornerstones of credit provision. It collects data, from other units or directly from clients, and it receives business requirements and operational constraints both from other units. Its main function is to construct forward-looking views of credit risk that is delivered e.g. via credit risk models. This function is the most clear-cut (and relatively thin compared to the other two - indicated with its slightly smaller size) but its importance in the credit provision process is significant.

These sub-units and their relation and information sharing are indicated in the following diagram:

How to Build a Financial Services Taxonomy

We have seen in the previous sections a wide range of perspectives on how the financial system is “composed”. We looked at regulatory schemes, industry schemes, official statistics views and some select deep-dives. How can we pull these disparate views together?

Let us first revisit what we are after: A flexible financial services taxonomy that can help us understand both existing and evolving financial system developments. The first order of business is to define what is being classified. There is no unique choice, but we can get useful hints from the analysis of Business Model Risk. The central object to classify is the Value Proposition of a given product or service which is obtained by addressing the need of a client segment using a range of internal resources and activities. The challenge is that there is no simple enumeration of elementary value propositions (financial needs). To address this we need to identify a range of useful taxonomic dimensions or aspects.

The financial system exists to support certain economic needs by diverse agents, so any taxonomy will invariably need to address the range of such entities and their respective needs. In principle, economic actors could engage directly, possibly with the support of pure utility platforms. Indeed, cash transactions using sovereign paper money are a good example of such a peer-to-peer arrangement. Yet more complex needs in current systems are addressed with the help of financial intermediaries 8. The role of financial intermediaries is precisely to enable diverse economic actors to engage independently of each other (e.g. with an intermediating bank or a stock exchange).

Who has a Financial Need?

Who needs financial services? This taxonomic dimension answers the question: Who has a financial need. The answer establishes who are the economic actors directly involved as consumers or clients. Needless to say that economic entities and their needs vary enormously in time and space. A good proxy is a categorization of real persons (e.g. demographically) and of legal entities (the different types of for-profit entities and the different types of public sector entities).

Yet financial needs are not in one-to-one correspondence with actor type. We have seen that it is individuals that might find utility in a pension fund structure as legal entities do not normally retire but borrowing and lending is also something for-profit and public sector legal entities engage in. It is thus important to have a dimension that focuses on the nature of financial needs.

What is the Financial Need?

Each and every “Who” will have a menu of financial needs. This may be e.g., Lending or Borrowing to accelerate or postpone consumption, Monetary Payments to facilitate economic exchanges within or across monetary systems, various forms of Insurance to mitigate and diversify risks etc.

Financial needs may have a temporal dimension (short / long term needs), may make reference to real / financial assets or be purely monetary etc.

A theoretical classification of financial needs into more primary elements might use the following decomposition:

- managing the present financial state, which, broadly speaking, means enabling payments, performing accounting, acquiring market intelligence etc. and

- managing future states, which, again broadly speaking, means performing portfolio allocation and managing risk

In any case, the matrix of Client-Needs is the central element of the taxonomy as it captures the value proposition that any financial service must deliver. The additional complication is the How such a value proposition is delivered. We have seen that there is both bundling of activities (which may or may not be strictly required) and possible substitution.

How is the Financial Need served?

This concerns how financial system entities solve a given Client-Need problem. It is more internally focused, on the procedures, activities and resources required. For example the different platforms, infrastructure, legal instruments, financial contracts etc. Illustratively, the various needs will translate into specific requirements for:

- Facilitating and Providing market knowledge (trading platforms, advisory services)

- Providing transaction efficiency (payment/settlement platforms, back-office accounting)

- Managing credit risk (ex-ante preventing non-repayment of funds)

- Providing contract enforcement (servicing contracts)

- Managing liquidity risk (cash flow timing mismatches)

- Managing market risk (volatility of market prices)

- Managing interest rate risk (volatility of the cost of money)

- Managing other contingencies and risks (insurance of various types)

We encountered already human professions involved in orchestrating the “How” a financial need is solved. We have also seen that individuals can organize according to various patterns and business models. This third taxonomic dimension essentially answers the question: How are those solving the financial needs of economic actors organized? This entails a financial intermediary taxonomy (business models, organizational structure, regulatory regime) which captures the different ways in which individuals and underlying resources and technologies can be orchestrated to deliver the desired solutions.

The How and by Whom is a Client-Need serviced are intermingled. We already noted that this is the result of two factors: the multiplicity and substitution of solutions and the possibility to bundle various services. We have seen that Bank Lending, Cash Securitisation and Synthetic Securitisation can all achieve credit risk exposure and there is significant flexibility of combining business lines (e.g. both Payments, Savings and Lending) within the same economic entity.

Yet ultimately the “by Whom” dimension suffers from circularity. The implication is that from an analytical perspective, it is the nature of economic agents and their financial needs in any given economic context and the menu of equivalent ways to address them are the two more fundamental dimensions.

The above notwithstanding, the governance of the eventual financial intermediary conglomerate that delivers financial solutions is also a very important consideration.

The internal structure and the positioning of financial intermediaries in the wider market sets the scene for the alignment (or conflict) of interests of internal and external stakeholders and to some degree it dictates the necessary regulatory regime. The How and by Whom financial needs are served leads to an important second-order taxonomy of What can go Wrong?. This taxonomy is, alas, outside the scope of this post.

Towards a Faceted Taxonomy of Financial Services

Mathematically, a hierarchical taxonomy is a tree structure that classifies a given set of objects on the basis of their attributes. It is sometimes also named a containment hierarchy. At the very top of this structure is the most generic, root node, that encompasses all objects. Nodes below the root node are increasingly more specific classifications that apply to subsets of the total set of classified objects.

A taxonomic tree is more than a tree structure. Think e.g., of file systems. They provide hierarchical containers (directories) and objects (files). But directories can be empty and the objects organized need not be homogeneous (text files, images etc.). Their only common feature is being a file. The different levels of the hierarchy need not follow a class inclusion pattern. Categories must be related to one another via a class inclusion relation. The highest level of abstraction is the most inclusive and the lowest level of abstraction is the least inclusive. Different number of levels in different branches may be required to accommodate different levels of complexity. Further, subclasses must be mutually exclusive and jointly coextensive with the class they divide.

Ideally we want to achieve hard classification: each object belongs to a cluster or not. The alternative is soft clustering (or fuzzy clustering) where each object belongs to a category to a certain degree. The classification features can be observed by anybody familiar with the table of these features. All entities find a unique place in the system, and the system implies a list of all possible entities.

As it has been alluded to already, a single hierarchical classification dimension is unlikely to capture the diversity of financial system manifestations. The standard information management solution for more complex taxonomic challenges is to use a Faceted Taxonomy. One way to think about such taxonomies is as classification trees living in parallel, one for each dimension or aspect that is being organized. Objects are classified by identifying their attributes within each of the tree.

We can characterize this as a function $f$,

$$ f : (\mbox{Client}, \mbox{Need}, \mbox{Solution Type}) \rightarrow { \mbox{Intermediary Type}} $$ where each of the input arguments $\mbox{Client}, \mbox{Need}, \mbox{Solution Type}$ a Categorical Variable , each with its own hierarchical structure, while the output value is a set of entities that are active in this subset of financial activities.

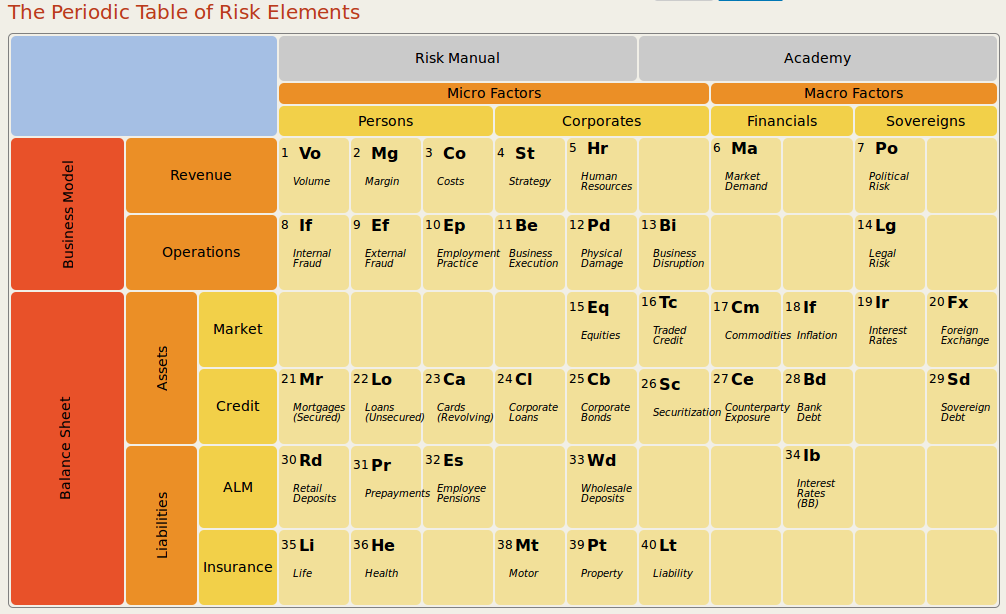

A simple manifestation of a faceted taxonomy that is very familiar is a matrix structure. This is effectively a two-dimensional taxonomy that may also support limited hierarchies. A visually interesting such representation that is focused on capturing risks along two different dimensions is the Periodic Table of Risk Elements:

References

-

Connecting The Dots: Economic Networks as Property Graphs ↩︎

-

IMF 2014, Shadow Banking Around the Globe, How Large and How Risky ↩︎

-

IMF 2017, Fintech and Financial Services: Initial Considerations ↩︎

-

A. Carstens (BIS 2018), Big tech in finance and new challenges for public policy ↩︎

-

Open Risk WP 09: Federated Credit Systems, Part I: Unbundling The Credit Provision Business Model ↩︎

-

We leave decentralized peer-to-peer (P2P) systems out of scope in this review. It is conceivable that digitization will enable P2P architectures that were heretofore non-viable without intermediaries. ↩︎