Thousands of possible social media platforms - but is anyone actually good?

In this post we explore the configuration space of possible social media platforms. We show that already with the known possible design choices there are multiple thousands of possibilities. Are better social media experiences to be found within this vast space or do we need an even more fundamental rethink? And how can we go about finding out?

Over the past two decades with the rapid diffusion of digital technologies billions of people changed behaviors. Almost everybody now is spending considerable time online, interacting with other people in newly invented social media. Diverse software platforms enable exchanges of all sorts of information over internet network infrastructures. Given the massive adoption there is little doubt that people derive meaningful utility from social media. At the same time a range of seriously negative impacts is becoming increasingly clear.

There are dozens of different social media platforms that have become popular at various points (some already long forgotten) and they vary in significant aspects of their design. Design choices that sometimes seem trivial can have significant impact on user experience and over time have significant psychological impact. See for example the role of infinite scrolling 1, which is a fairly specific choice about how content from the social media platform is presented to users.

To catalog all the detailed social media design choices is a fool’s errand: While social media platforms are not the proverbial rocket science in terms of complexity, they do involve a large number of software subcomponents and there are simply too many individual elements to enumerate. But if we keep things at a higher, conceptual level, the task becomes more manageable. The result is still useful as it gives us a sense of the order of magnitude of possibilities.

Defining the configuration space of social media platforms

A good starting point for understanding the configuration space of social media platforms is an actual specification of a social media protocol. Thankfully there are currently significant efforts to create open source social media (see e.g., ActivityPub and ATProto) and those efforts document their choices, data models etc. publicly 2 3.

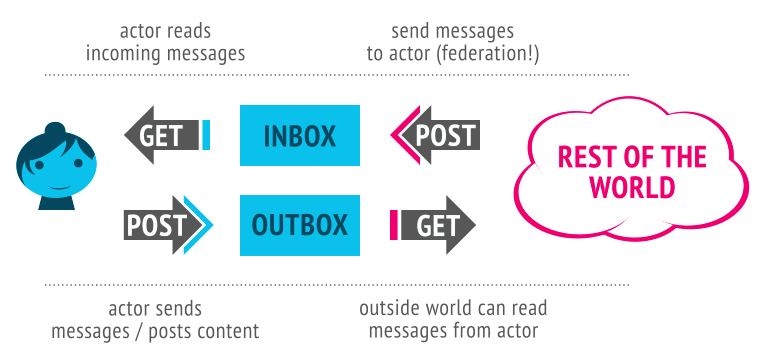

We will use the ActivityPub spec to scaffold the discussion. While the actual specification (and the ancillary ActivityStreams spec) are too detailed for our purposes, it does help abstract some important high level architectural elements, which in turn will help us enumerate a set of relevant design choices.

The Actor abstraction

This is the starting point and maybe the fundamental abstraction of social media platforms. People (platform users) get to have an account that is linked to them specifically and is obtained after registering with platform. A related (but not identical) abstraction is that of an Actor. This is a functionality of the platform that enables a user to perform an action, e.g., post something.

NB: There is no one-to-one correspondence between users and actors. A user can be associated with several actors and an actor can represent a group of users.

The Activity abstraction

Actors do things, and what they do are Activities. Which in practice means creating (materializing) content and sharing it with other users on the social media platform. This maybe a post that is long and substantive enough to be an article, a video that could be a short documentary, or just a simple like. The nature of an Activity is shaped by the mechanics of information creation (e.g. what type of data) and how it propagates (what are the effects it has) in the platform (which in turn largely shapes how users experience it).

The Social Graph abstraction

Last but not least, the so-called social graph is the defining feature of social networks that distinguishes them from other types of online platforms where Actors (users) perform Activities (generate content), such as forums or wiki’s.

The social graph, in a social media context, is simply the representation of how users (via their Actors) are linked to each other. This linkage determines to a significant degree how the user experience the platform, as it filters and narrows down the potentially vast amount of content being shared.

Enumerating Social Media Platform design choices

We are now equipped with a basic analytic framework to help us enumerate design choices. The order of presentation will not imply a ranking of importance. There is also no attempt to evaluate which among the options for each design choice is “better”.

User Identity (2x choices)

It is maybe appropriate to start with options and choices around the meaning and function of User Profiles. There is a range of options of what a user profile means, what it includes, how “real” or verified it is and what fraction of it is displayed to whom. Clearly the possible options are vast, but we can conservatively narrow them to only two:

- pseudonymous profiles (potentially including algorithmic bots) that do not explicitly link users to their real life identity, hence the social media platform acquires an element of a “make believe” world

- accounts that require and display a real (human) identity, linking the account to an actual person (or organization / legal person representative)

Platform Ownership Pattern (3x choices)

This element concerns the important question of who builds the platform (incurring upfront costs), and who operates the platform (again, incurring ongoing costs). This is on the one hand a technical aspect that regular users may not particularly care about but, on the other hand it defines the social, political and economic context in which a platform operates (defining incentives, options and liabilities for platform owners and operators).

Broadly speaking we can differentiate between three ownership patterns:

- centralized models, where a single party is building and operating the platform

- decentralized models, where multiple parties can build and operate instances that participate in some form of syndication or federation

- distributed or peer-to-peer models, where each individual user operates their own instance

Who Pays, or what is the business model (3x choices)

This is a question related to, but distinct from the ownership question. The question is how are the costs of building and maintaining the platform to be met (and whether financial profit is part of it), in other words, who pays and why.

There are at least three answers:

- advertisers pay the platform owners in order to use the platform to target platform users

- users pay the platform owners, in order to communicate (in the same way e.g. they pay for telephone service). Here we also have the possibility of peer-to-peer networks where users pay to operate their own instances

- the public sector pays in order to provide public goods

Mixing business models is, in-principle, possible: E.g. newspapers have income that is a combination of advertisement and user fees.

Platform Transparency (2x choices)

A technical aspect that is not particularly visible to regular users but has important implications for the nature of the platform is how transparent its operations. This attribute is particularly important when the platform employs significant algorithmic components that have material impact in its function. Again a binary choice captures the minimal granularity that is available here:

- open source platforms, where anybody can inspect the code on which the platform runs

- closed source platforms, where inspection of the code is only possible by permission from platform owners

NB: Here is there is a technical nuance an open source code that actually runs an instance may have been modified.

Platform Interoperability (2x choices)

The significance of this aspect has grown significantly in importance as platforms mature and is indicative of emergent issues plaguing rapidly changing behaviors. Once people have invested significant time and effort in creating and sharing content, building out their social graph etc. the question arises to what extent users have the option to migrate this social media activity to another platform. In this respect we can classify platforms as:

- closed, non-interoperable platforms, where user identity, user content and user social graph are difficult to transfer

- open, interoperable platforms, where migration/transfer paths are explicitly supported

Primary User Intent (3x choices)

Why are people on social media? Where does the utility come from? This is a hairy topic, but we can sketch a few important distinct forms of user intent on which to base the discussion:

- being informed and/or educated (a news function)

- socializing, discussing, playing, being entertained (a cafe type function)

- professional objectives (a networking function)

An interesting aspect of this dimension is that platform designs cannot rigidly constrain how and why people will use the platform. Design elements, moderation etc. can hint and nudge users in particular directions but there is also an element of emergent behavior.

Primary Media Focus (4x choices)

Possible choices in the “media” part of “social media” are actually fairly well-defined because they concern the concrete format and type of the data exchanged by users in activities. In internet/web technologies a central technical specification is the concept of MIME types (Multipurpose Internet Mail Extensions) 4. It is the standardized way of describing the type and format of data being exchanged over the internet. As part of its implementation of Activities, a platform must support both user generation of content in a given format, the exchange of data between users, and the display of a media type by the receiving users.

There are four main media types that are currently used in social media context:

- text (leading e.g. to micro-blogging platforms)

- images (e.g. photo sharing platforms)

- audio (music sharing platforms)

- video (both short / long durations)

Social media platforms can in principle enable exchanging any of the above (and many do) but over time, it seems that that media specialization has been a differentiating factor between platforms. The reasons for this segmentation likely include the importance for users of having a uniform interface to create and absorb information but also practical constraints associated in each format.

If we were to take the combinations of possible media choices literally we would have $2^4 - 1 = 15$ possible platforms on the basis of their set of supported media. But we make a conservative estimate and reduce the number of choices to only 4, one for each primary or preferred media that characterizes a platform.

Social Graph Structure (2x)

We mentioned already that the social graph is important for defining a social media platform. The most basic classification would distinguish between two options:

- directed graph (users can follow without being followed)

- undirected graph (users can only have symmetric connections)

There are further ramifications around the social graph that have to do with how links can be established (or avoided). This includes features such as users asking for permission to follow, users being able to block other users at their discretion etc.

Moderation Structure (2x)

The social graph plays already an initial filtering role (Actors can only exchange information with connected Actors) but there are at least two more possibilities that enable further filtering of information:

- human moderation, this involves employing specialized persons having elevated abilities to reconfigure who can share what within the platform

- algorithmic moderation, this is an attempt to automate the process of reconfiguring information flow which benefits from reduced costs (and potentially is more consistent) but suffers from limitations of algorithms (generally simplistic and biased)

Information Display (2x)

There is considerable freedom in how to display information exchange in the platform (after allowing for all the filters). Especially when the number of participants increases, the amount of information shared skyrockets, giving rise to the firehose phenomenon (there is simply too much information for an individual to absorb).

One important aspect of information flow is the temporal profile of exchanges. While it is by no means required, platforms tend to emphasize recent information exchanges. This creates at least two different ways of organizing how information is displayed.

- the timeline or feed “illusion” that places primary emphasis on temporal information flow. This can be arranged in a purely chronological flow for all exchanges, may have an algorithmic filtering mechanism. It is also a display choice whether to adopt so-called infinite scrolling or some form of pagination.

- a platform may employ hierarchical, grouped display of content (that might be e.g., subject/category based) to modulate the significance of purely temporal ordering

Information Density and Complexity (2x)

The key issue here is that the density and complexity of information that can be meaningfully displayed on a screen depends on screen size. This leads to a bifurcation of possible approaches.

- Desktop oriented. Originally social media platforms were desktop oriented as these were the only available personal computing devices!. Large screen sizes constrain the time and location one can interact with social media platforms but offer plenty of screen “real estate” to display complex information.

- Mobile first. With the explosion of mobile small portable screen reduce the spatio-temporal constraints on interactions on social media platforms. Yet inevitably this necessitated simplified information displays.

Further Platform differentiators

There are more characteristics that can differentiate social media platforms but were not included in the above enumeration as they concern more subtle choices.

- Content discovery mechanisms: how users find accounts and content relies on search capabilities, the use of keywords (hashtags) and algorithms.

- Direct (voice)messaging over social media platforms provides the ability to emulate other communication platforms (telephony).

- The degree to which the platform facilitates multilingual exchanges (e.g., via automated translation).

The thorny issue of data privacy

A recurring theme in social media architecture discussions is the issue of data privacy, namely defining who can access what data exchanged by platform users. The social graph itself can play a natural role in designing privacy rules. A platform may adopt the design that everything is public by default, which reduces the social graph to an information filter. A generalized framework that aims to address the space of possibilities in this direction is provided by the OCapN framework 5.

Is any of combination of these designs choices actually good?

A simple multiplication of all the above design choices shows that there are thousands of possible combinations, thus a huge configuration space. For the curious the actual number is 13824 possible social media platforms!!

A multiplication implies that the choices are indeed independent (can be combined arbitrarily from a menu). This will not be strictly true. Yet together with all further subtleties we have discarded in the journey, this indicates that we indeed have a very rich space.

Compounding the challenge is that we may not even know all the relevant factors. The fact that most of our current knowledge of social media platforms has been shaped during a period of extreme dominance of a handful of platforms suggests there may be significant design elements we have not even identified yet. One example could be social media where the location of users plays a more meaningful role, departing from the paradigm of a virtual space that knows no geographical boundaries.

Where does this overabundance of options lead us? A first remark might be that it might not be wise to bundle every and all social media platforms into one category. Some of the design choices might indeed be more critical than others, leading to distinct islands in configuration space, which could be recognized by assigning distinct names to these super-categories. Yet at this moment is not easy to discern which are the most critical decisions.

More importantly, since the overarching objective is the development of “good” social media, what would be the best strategy to achieve that? There are two important challenges.

- First is the question of defining “good”. The major commercial (adtech) social media platforms had an easy task in this respect: they are constantly optimizing for more financial return. Features are trialled and adopted or discarded with so-called A/B testing, which ultimately boils down to achieving more “engagement” and selling more ads. Social return6 for a social media platform is harder to define and measure, but therein lies the real challenge when developing a new generation of platforms that provide the undeniable utility without incurring the heavy social cost.

- The second challenge is how to achieve goodness, assuming it has been defined to a practical degree. A key reason for this difficulty is the important emergent behavior of such platforms. This is not a mysterious phenomenon, it manifests whenever large number of people interact. The implication is that it is not easy to predict how, under conditions of wide adoption, diverse actors will operate and shape the nature of exchanges and behaviors. Given the uncertainty and novelty of the challenge, and the vast configuration space it would seem that the best answer is simply: by trial and error:

There might be really only one way to find out which of the thousands of different possible social media platforms are good. Namely, to try them out and report back!

But how can such a trial and error approach work given the cost and other practical difficulties, including for example that strong network and sunk-costs effects mean people would be reluctant to participate in large numbers of new platforms?

One conceptual pattern that might help achieve large scale experimentation, over time, is to have widely accessible, easily deployable, readily reconfigurable, open source, social media platforms that have the gathering and reporting of relevant assessment metrics built-in. In other words, to think, devise and deploy meta-platforms, social media infrastructures that admit substantial customizations with as little friction as possible for both users and owner/operators.