What can Inka Quipus teach us about data management

What can Inka Quipus teach us about data management

If, as it is most probable, you are a typical person, chances are that your knowledge of ancient Peruvian culture is a bit rusty!

Maybe you have some vague high-school memories of an extensive but somewhat “backward” empire (as seen by the then European peoples) that was conquered and then asset-stripped by a handful of aggressive Spanish conquistadors.

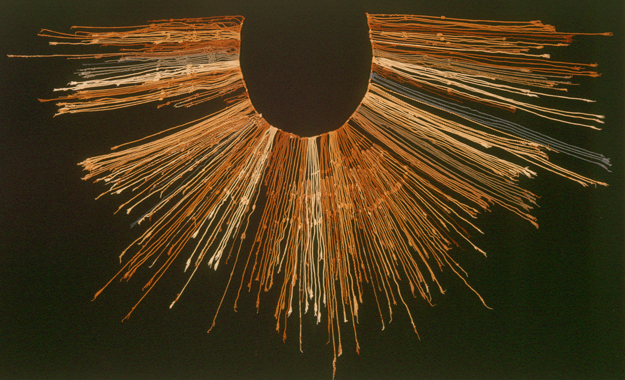

Or maybe your best preserved memory is the excitement of reading von Daniken’s rampant speculations about the Nazca lines and ancient extraterrestrial spaceports. But unless it happened that at some point later in life you heard about the work of Prof. Urton and his collaborators, most likely you have no idea what an Incan Quipu is (see image).

Ancient Peruvian civilizations never developed writing, but by the time of the Incas they did have an elaborate counting and recording system that was using Quipus (collections of knotty strings) as its physical data storage mechanism. As per wikipedia, a Quipu usually consists of a number of cotton or camelid fiber cords. It contains categorized information based on dimensions like color, order and number. The Inca, in particular, used knots tied in a decimal positional system, hence they were able to store numbers and other values in Quipu cords. Depending on its use and the amount of information it stored, a given Quipu may have anywhere from a few to several thousand cords.

While the precise encoding scheme is still not known, we know that the system was effective enough to allow the Incas to manage a highly organized agricultural empire encompassing no less than 20 million souls, which geographically extended from modern day Equador all the way to Chile.

Lesson 1: Without metadata, your data records will not make it into history

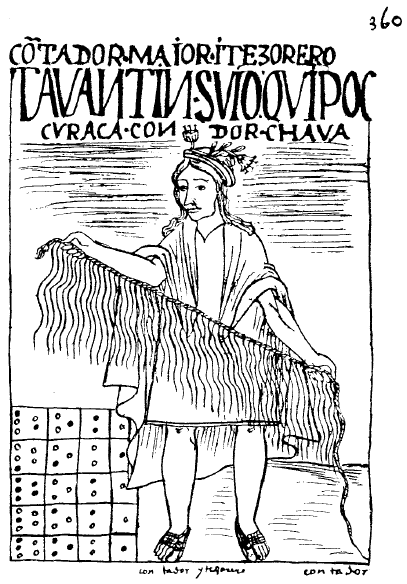

While there are still plenty of quipus around, there is no meta-data device that would allow deciphering the data. The Incas themselves apparently learned the ropes (forgive the pun) via oral traditions. There was a specialized class of accountants called quipucamayocs. Quipucamayocs were a distinct class of people (all male), apparently fifty to sixty in number, that knew how to encode and decode the accounting data.

We can speculate that the Quipucamayocs had very high job security and all sorts of perks, like residing in the few urban administrative centres of the Inca empire and not having to work the fields. While this was (probably) good for them, it was eventually not very good for the preservation of the empire’s data (so called Institutional Memory). In modern terms, replace the disruption brought on by the conquistadors with, e.g., a merger or acquisition event affecting a commercial entity (barbarians at the gate) and you have the conditions for some serious legacy database problems.

Database metadata is the information that describes the structure, organization, and characteristics of data within a database. In a relational database it includes details like the table names, the column data types and the relationships between data. How could the Incas have achieved describing the Quipu metadata given that they were lacking writing systems in the first place? One can let the imagination run wild, but a physical Rosetta Stone that would e.g., have side-by-side depictions of Quipu configurations along side pictograms representing the situations being recorded might have done the job.

Lesson 2: Human readable encoding of data is advantageous

While we don’t know what the numbers encoded, we know through the work of the Aschers (a pioneering couple of ethnomathematicians that studied extensively the Quipus) and others, that they were using a decimal system. For example the number 42 would be represented by four short type knots and two long type knots. In other words, anybody can immediately make sense of the data (in fact literally!). Tactile representation of data is the ultimate in accessibility.

Why would one today need human inspection of data in the first place? A key reason which often motivates inspection of data is data quality (or the lack thereof) and the need for human intelligence and context awareness to assess whether a given data set is fit for purpose. In modern computing systems a choice for low level binary encoding has been made long ago to optimally match the properties of silicon digital devices. Yet there is still considerable freedom on how to represent information at higher level (e.g. in files or document databases). For example one can use the verbose XML format or the more terse (and more readable by humans) JSON format. While both XML And JSON are equally readable from a machine perspective, the latter is more suitable for human consumption and hence preferred when human interaction with the data is required.

But readability may come with a cost (and there is potentially an implicit conflict here with Lesson 1). Namely The reason XML and other related concepts such as RDF are less easily readable is because the integrate a lot of additional information (they are self-documenting).

Lesson 3: A document store is more flexible than the classic relational database

If you look at a Quipu more closely (image below) you see that:

- all of its strands are tied on one side only

- the length of each strand may vary

Thinking in terms of a standard database you might be tempted to think of each Quipu “instance” as one giant database table and each of its strands as one row of data. But the flexibility of the untied end means that the schema can be modified very easily. The structure is more akin to a graph database or a document database than a table. For example if a new crop has been planted that needs larger numbers to be accounted for (and we thus need more space per each village record), we can simply start attaching longer strands!

This reminds us that the growing popularity of so-called NoSQL databases was for similar reasons: offering more flexibility when modifying the schema of the database. On the other hand we can see why insisting on controlled uniformity (here uniform length of strings) might carry less cognitive load and thus allow working with significantly larger-sized Quipus.

Lesson 4: There is ancient logic to append-only databases

It is thought that the Quipus were write-only. It sounds indeed plausible that whatever the usage pattern of the Quipus, it did not involve untying knots (except possibly when an egregious recording error was made). In other words, out of the well-known database CRUD operation set (create, read, update, and delete), the Incas had effectively dropped the Update operation. The Delete operation probably involved chucking the strand or maybe tying a delete (ignore) tag at its end. Hence the Incas had a drastically simplified the set of data operations, which reminds us of the rising popularity of the append-only technologies.

People who grew up while the size of hard disks and RAM where still counted in M’s (megabytes) might be horrified with the idea of a database that only grows and never updates! But we have moved since quite a few logarithmic scale letters (from Mega -> Giga -> Tera -> Peta -> Exa). Append-only database might be the most robust solution for some data applications.

There you have it, from the depths of time, timeless advice (or at least food-for-thought) on how to design the database technologies of the future!

Comment

If you want to comment on this post you can do so on Reddit or alternatively at the Open Risk Commons. Please note that you will need a Reddit or Open Risk Commons account respectively to be able to comment!